Sunday, June 27, 2010

Naked Capitaism: Deficit Doves, the Gift that Keeps on Giving

The first section of this post is by Warren Mosler, the President of Valance Co. who writes for New Deal 2.0

Deficit doves are doing more harm than the hawks — here’s what they need to know.

The deficit hawks are prevailing. The economy remains an economic and social disaster. Medicare has already been cut by the Democratic majority in the new health care bill. Social security is now under attack by the new bipartisan Congressional Commission on Fiscal Sustainability and Reform. Meanwhile, the media tries to present a balanced approach, pairing deficit hawks with deficit doves.

But the deficit hawks aren’t the problem. They do the best they can with arguments that feature empty rhetoric supported by the underlying assumption that deficits are ‘bad.’

Actually, it’s the well-intentioned but misinformed deficit doves featured by the media that may be doing the most harm. They don’t understand actual monetary operations and reserve accounting, and therefore incorporate the same fundamentally incorrect assumptions as the deficit hawks. They agree deficits are ‘bad,’ but try to argue that’s the case only in the long term. They agree that deficits can be too high, but try to argue they have been higher, particularly in World War II, and therefore larger deficits should be easily manageable, while agreeing there is a level that could not be manageable. They agree markets could be ‘unfriendly’ and a lack of confidence could translate into far higher interest rates, but argue that the current low rates for Treasury securities are the markets telling us that at least for now confidence is high indicating markets are eager to fund current deficits. And they agree that ‘bang for the buck’ matters and support tax cuts and spending increases based on higher multipliers.

The problem is that the two sides of the story are in fact fundamentally on the same side. The media does not feature the true deficit dove story. Nor do any of the true doves have even a small piece of the administration’s ear, or the ear of anyone in Congress willing to speak out. There are maybe a hundred true doves, including many senior economics professors. The problem is this professional, highly educated, highly experienced collection of true doves does not get a fair hearing.

The true deficit dove positions include:

1. Since government spending is merely a matter of changing numbers in bank accounts on its own spread sheet, there is no solvency issue or sustainability issue

2. The right size deficit is the one that coincides with our stated goals of full employment and price stability.

3. Interest rates for government are set by the government, and not by the market place.

4. Bang for the buck considerations are moot as the size of the deficit per se is not an issue.

The answer to why the true doves capable of articulating the above points don’t’ get a fair hearing may be credentials. My BA in Economics from the University of Connecticut in 1971 doesn’t cut it, nor the fact that the very large fund I managed was the highest rated firm for the time I ran it. And my net worth never getting anywhere near a billion hasn’t helped either. Seems billionaires get celebrity status and lots of airtime for just about anything they want to say.

The same is true of the economics professors who’ve got it right. Without being from and at the usual ‘top tier’ schools, none can even get published in main stream economics journals, where submissions featuring obvious accounting realities are routinely rejected. In fact, any economist who states accounting identities and operational realities such as ‘deficits = savings’ or ‘loans create deposits’ or ‘Federal spending is not constrained by revenues’ is immediately labeled ‘heterodox’ and unworthy of serious mainstream consideration. Even the late Wynne Godley, who did have reasonable credentials as head of Cambridge Economics, and was the number one UK economics forecaster, was labeled ‘unorthodox’ because his mathematical models featured the deficits = savings accounting identity.

My three proposals that can immediately turn the tide and get us back to full employment and prosperity remain:

1. A full payroll tax (fica) holiday

2. $150 billion of Federal revenue sharing to the States on a per capita basis

3. An $8/hr Federally funded job for anyone willing and able to work to facilitate the transition from unemployment to private sector employment.

The only thing between today’s state of the economy and unimagined prosperity is the space between the ears of policy makers that’s filled with the deficit hawk rhetoric, and unfortunately further supported by the rhetoric of the deficit doves the media selects to present the ‘opposing view.’

Yves here. Mosler wrote this piece to address the debate over the federal budget deficits in the US, which meant he could skip over some important caveats.

Modern Monetary Theory does describe how the world works in a fiat currency regime, meaning the “government” is the issuer of sovereign currency. Despite all the hyperventilating about default, governments that issue their own currency will never be forced to default (note that Greece, Spain, Ireland, and California are not in this position). They can create a lot of inflation, but that is a separate issue.

The times in the modern era when sovereign states have defaulted is:

1. Under a gold standard

2. When they either are not currency issuers OR have adopted a currency they do not control (eg. countries like Argentina that dollarized their economies)

3. Countries that have overly large banking sectors relative to GDP AND those banks have large liabilities in foreign currencies AND those banks have major solvency problems (Iceland, this would also be the reason for a UK default)

The lone exception is the Russia default of 1998, which remains a bizarre, opportunistic incident. Russia’s sovereign debt was under 20% of GDP, and there was no reason for it to have defaulted, even if its debt levels had been higher.

Now to a general point about MMT. The negative responses to it are almost reflexive, shoot the messenger: deficit = bad, we aren’t prepared to listen to anyone who says otherwise.

Sorry, gang, it IS more complicated than that. We’ve provided this formula before:

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance – Current Account Balance = 0

Now let’s consider what has happened in the US, and some other advanced economies. Our corporations, in their infinite wisdom, have decided increasingly to offshore and outsource, which means move operations outside the US and to turn big chunks of their operations over to other companies, again often foreign ones.

Let’s go back to the formula. First result is that we have a current account deficit. So that means that the sum of the other two parts of the economy, the private sector plus the public sector will run deficits, as in borrow more than they spend. Maybe one is a net saver, the other a bigger net borrower, or both are net borrowers. But at least one sector will be a net borrower.

But let’s consider another set of issues. The fixation of public companies on quarterly earnings plus the offshoring/outsourcing phenomena have led them to become net savers, even in expansions (see here for a long-form discussion). Normally, the household sector is a net saver (households generally try to save for retirement and for emergencies). Most readers appear to implicitly assume that those funds should be used by business, that government borrowing crowds out private sector borrowing. But while INDIVIDUAL businesses do borrow, recall they also generate cash. The trend, even in periods of growth, when businesses as a whole ought to be borrowing and investing in growth, is instead that they are net savers.

In that scenario, even if the US had no trade deficit, the government would need to run a deficit to accommodate the desire of the private sector to save. The alternative would be that the US would need to go from its assumed trade balance to a trade surplus. That would happen through a fall in prices and wages in its tradeable goods sector (which can happen via domestic deflation, which will make debt burdens worse in real terms, or a fall in the dollar) and/or an increase in productivity so that our exports gained market share.

Now the private sector in the US is deleveraging, which and reducing debt is tantamount to saving. We have pointed out that the euro would likely have to fall to 60 to 80 cents to the dollar to prevent the eurozone from falling into deflation (which will make debt levels in real terms worse and almost certainly precipitate the defaults that the austerity programs being implemented are meant to avoid.

The certain continued fall in the euro (the trajectory is a given, the open questions are how far and how fast), and China’s signaling that it is likely to devalue its currency if the euro falls materially means the dollar is likely to remain strong, Right now, every country with overly high debt levels wants to break glass, weaken currency, and use exports to provide it with some lift to offset the contractionary impact of deleveraging. It appears unlikely that the US will be able to play that game. Odds are high that we will continue to be a net importer.

So, if we decide to run government surpluses now, the result is almost certain to be deflation, at best a Japan-type stagnation with high unemployment (and the US has far less social cohesion than Japan does), at worst a deflationary downspiral. But in either case, austerity becomes self-defeating. The value of outstanding debt rises as prices fall and GDP contracts. Default becomes more likely, and as defaults rise, banks become more impaired, investors more cautious, and the downturn can easily accelerate and become self-reinforcing.

Now some readers are correctly concerned about the wisdom of letting the cohort in DC spend more, given our misadventures in the Middle East, and healthcare “reform” serving as a Trojan horse for further entrenchment and enrichment of Big Pharma and the heath insurers. I am certainly not keen about handing a blank check to the likes of Geithner (oh wait, we did that already, it was called the TARP). We also need to keep pressure high on the need to reform governing structures.

As much as the logic of continued government spending is unpalatable to many, be careful what you wish for. If you think the economy now is not so hot, just wait to see what happens if deflation takes hold.

Saturday, June 5, 2010

I think it is in some ways unfortunate that economics is caught in a Keynesian/Monetarist (or classical) binary. Broadly speaking the debate is about whether government can have a positive effect on the workings of the economy. The problem is that this binary does not capture the full spectrum of attitudes towards government and it causes some philosophical problems for any leftists cum economists. Tiny, tiny, minority they may be.

Simplistically speaking, I subscribe to the Marxian point that the state is a "committee for the management of the affairs of the bourgeois". Oddly, I think there is a lot of overlap in the way I see the world as your walk-a-day libertarian who similarly sees governments as constraining the potential of the world. In fact, the idea that governments are simply the tools of corporations is a large component of libertarian ideology. After all such things as bailouts, "regulatory capture", and even the Fed are all seen as distorting the playing field in favor of the politically connected few. I find myself more often than not nodding in agreement with libertarian or Hayekian critiques of how the current system is managed.

Libertarians, however, lose me when they start prescribing solutions. In a nutshell their solution to the problems with capitalism is simply more capitalism. The intellectual work is simple, governments distort the natural process of the market and once the market is set free from government control manna will rain from heaven.

But what if you don't believe that the solution is more capitalism? Solutions become very messy. The problem is that, in a universe of atomistic firms and households (the world of the economist) the only point of conscious intervention in the economy is government. So we are stuck putting lipstick on a pig so long as we are forced to defend the efficacy of government. I, personally, am willing to hold my nose and pull the lever. A defense of government intervention is--baring some kind of miracle of theory or reality--a defense of conscious intervention into our own history.

However--and I want to point out I'm not entirely cynical about this--there is always an endless stream of caveats. For instance, from the EconSpeak post above after talking about the "center-to-left prescription for the recession Mr Dorman goes on to point out:

In a sense yes: those who make the decisions summon economic arguments to justify their actions. But who gets to make the decisions and what arguments they find appealing is not the outcome of academic seminars. What got us into this mess in the first place, and what now threatens to throw us back into the maelstrom, is the political hegemony of the “finance perspective”, the interests and outlook of those whose main concern is maximizing (and now simply protecting) the value of their financial assets.

Within the world of elite interests, this is almost a mass constituency. While the bulk of such assets are held by an infinitesimal few, perhaps the top 10-20% of the population in the industrialized countries have significant financial wealth and actively monitor their returns. Their understanding of how economies work and what priorities policy-makers should adhere to follow from their personal position. Inflation is a constant threat to asset-holders. They fear the laxity of central banks as well as the buildup of government debt, which can serve as an incentive to future inflation. They want their portfolios to have a component of absolutely risk-free government securities, and the very whisper of sovereign default chills them to the core. They believe in the inherent reasonableness of financial markets and believe that anyone who wishes to borrow from them should demonstrate their prudence and fiscal rectitude. They were willing to relax their principles temporarily during the panic, but now that they have caught their breath they want to see a return to “sound” practices. Governments will bend to their wishes not because they have better arguments, but because they hold power.

How do you get business done in such an environment? I have found myself disagreeing with Paul Krugman's call for a larger stimulus. It seems that within a democratic system the nature of compromise necessarily means any kind of stimulus would be too small. Whats more, the mishmash of the stimulus bill was qualitatively inadequate. So why should we insist that congress mismanage more stimulus? Here, though, it is not just my politics but my professional chauvinism that finds the process aggravating. As a side bar, I'm fairly certain that the last generation of economists have been preoccupied with monetary policy not only because the stagflation of the 70s was their founding trauma but because monetary policy is largely the sole technocratic purview of economists. Anyway, disagreeing with the call for more stimulus then means retreating into a weaker position that "in theory this would work."

The real solution to this impasse is not intellectual. It's political, for those of us who desperately do not want to be cynical about the role of government also have to assume that it is possible for political life to operate properly. What we ultimately need is a government--while not perfect--is something that can be believed in and trusted. I feel a great nostalgia for the immediate post war era when governments had proven they could respond to a crisis and there was--even in the US--a consensus about the legitimate role of government in economic life.

The 70s of course changed all that. The documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis' four part "The Century of the Self" traces the individualism of the baby boomer generation from its political expression to its transformation into "lifestyle consumerism" in which individualism get channeled and expressed through differentiated consumption goods. Curtis contends that Ronald Reagan's declaration that "Government is the problem" spoke precisely to this individualism which had been shaped over the turbulent and dysfunctional national politics of the 60s and 70s but had become cynical and satiated. I think, in a way, that process has been repeating itself or I suppose it is the new political reality. The new rise of libertarianism seems to be siphoning off significant proportion of people who should be properly left leaning. The critique is the same either way you go but but leaning right offers a simple and consistent prescription. Unfortunately, in the absence of something simple and coherent a functioning left requires some kind of demonstrable proof. That proof has been fairly short in coming over the last 30 years as Reagan's prophecy fulfills itself.

How I would deal with the European debt crisis.

The buying of Greek debt would not be inflationary since the ECB would effectively be sterilizing the purchase of Greek debt with the issuance of Eurozone debt. It would also relieve the fiscal pressure on the countries who are putting up government funds to help shore up the Eurozone. These countries could still--in partnership with the ECB--exercise control and impose all the austerity conditions they want.

This would also help push the Euro ever so slightly toward its full potential as a competitor currency of the dollar since it would finally create a true Eurozone debt instrument. Obviously, though, the market would not be very large or liquid but perhaps this market could be opened up to other countries. While the EU does not seem overly concerned with the problem of moral hazard it would be relatively easy to limit countries from taking advantage of this market if the EU actually started to enforce their rules governing debt to gdp ratios.

I am double minded about what interest rate to charge the Greeks. A penalty rate seems appropriate, but obviously that may only make it more difficult for Greece to pay down it's debts. At any rate, some kind of risk premium above what the ECB would get on the Eurozone instrument seems appropriate and would be profitable for the ECB. And if the Greeks finally do default? Well, then the Germans can put their real money to work.

Perhaps unfortunately, I do not run Europe and the ECB seems like a profoundly conservative and unimaginative institution. That may be a necessary thing in Europe, it may also be a major liability for Europe to have monetary policy nonexistent at the national level and unhelpful at the supra-national level. While the ECB has been engaged in what the Wall Street Journal calls a "stealth bailout" of Europeans banks holding Greek debt they may do well to push things further. Legal and political realities notwithstanding.

Don't Blame Fannie, Freddie, CRA or poor people

In the interest of being fair, the most compelling arguments for blaming fannie and freddie come from Charles Calomiris:

Charles Calomiris onEconTalk October 26th, 2009

and the paper By Edward Pinto they reference:

www.aei.org/docLib/Pinto-High-LTV-Subprime-Alt-A.pdf

I think that Calomiris is right to point out that Krugman's claim (talked about in the last article posted) that Fannie and Freddie did not make subprime loans because they were legally prohibited doesn't hold water, but who knows.

Anyway, below are a couple of old blog posts, all by way of or from the Economist's View blog. The final post, directly from Economist's View is the best one.

Kroszner: CRA & the Mortgage Crisis

By Barry Ritholtz - December 3rd, 2008, 11:53AM

Sayeth the man:

“Some critics of the CRA contend that by encouraging banking institutions to help meet the credit needs of lower-income borrowers and areas, the law pushed banking institutions to undertake high-risk mortgage lending. We have not yet seen empirical evidence to support these claims, nor has it been our experience in implementing the law over the past 30 years that the CRA has contributed to the erosion of safe and sound lending practices. In the remainder of my remarks, I will discuss some of our experiences with the CRA. I will also discuss the findings of a recent analysis of mortgage-related data by Federal Reserve staff that runs counter to the charge that the CRA was at the root of, or otherwise contributed in any substantive way, to the current subprime crisis . . .

“This result undermines the assertion by critics of the potential for a substantial role for the CRA in the subprime crisis. In other words, the very small share of all higher-priced loan originations that can reasonably be attributed to the CRA makes it hard to imagine how this law could have contributed in any meaningful way to the current subprime crisis.”

Be sure to read the entire speech by the Fed Governor here. He discusses the result of an exhaustive data analysis performed by the various Fed Banks looking into the CRA issue and sub-prime

Of course, now that the election is over, the usual parade of reality challenged nitwits won’t be interested in any hard data or professional analyses. The full 233 page report is available here.

Things Everyone In Chicago Knows...

June 3, 2010

Which happen not to be true.It was deeply depressing to see Raguram Rajan write this:

The tsunami of money directed by a US Congress, worried about growing income inequality, towards expanding low income housing, joined with the flood of foreign capital inflows to remove any discipline on home loans.

That’s a claim that has been refuted over and over again. But what happens, I believe, is that in Chicago they don’t listen at all to what the unbelievers say and write; and so the fact that those libruls in Congress caused the bubble is just part of what everyone knows, even though it’s not true.

Just to repeat the basic facts here:

1. The Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 was irrelevant to the subprime boom, which was overwhelmingly driven by loan originators not subject to the Act.

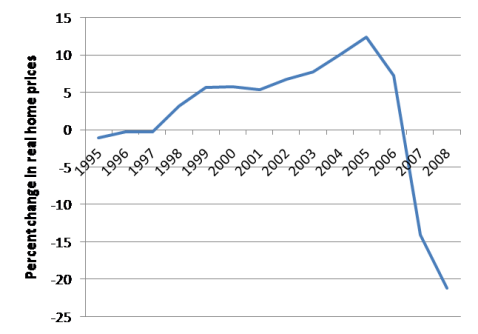

2. The housing bubble reached its point of maximum inflation in the middle years of the naughties:

Robert Shiller

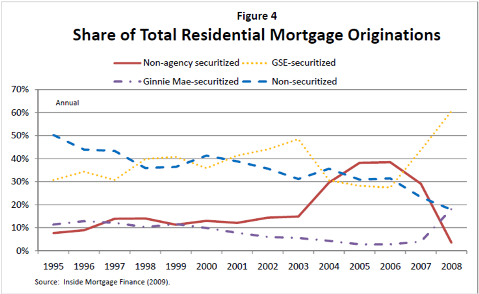

3. During those same years, Fannie and Freddie were sidelined by Congressional pressure, and saw a sharp drop in their share of securitization:

FCIC

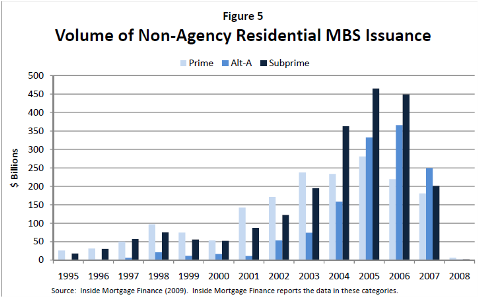

while securitization by private players surged:

FCIC

Of course, I imagine that this post, like everything else, will fail to penetrate the cone of silence. It’s convenient to believe that somehow, this is all Barney Frank’s fault; and so that belief will continue.

Once Again, It Wasn't Fannie and Freddie

Russ Roberts:

Krugman gets the facts wrong, by Russell Roberts: Back in July, as Fannie and Freddie were starting to implode, Krugman concluded that Fannie and Freddie weren't part of the subprime crisis:

But here’s the thing: Fannie and Freddie had nothing to do with the explosion of high-risk lending a few years ago, an explosion that dwarfed the S.& L. fiasco. In fact, Fannie and Freddie, after growing rapidly in the 1990s, largely faded from the scene during the height of the housing bubble.

Partly that’s because regulators, responding to accounting scandals at the companies, placed temporary restraints on both Fannie and Freddie that curtailed their lending just as housing prices were really taking off. Also, they didn’t do any subprime lending, because they can’t: the definition of a subprime loan is precisely a loan that doesn’t meet the requirement, imposed by law, that Fannie and Freddie buy only mortgages issued to borrowers who made substantial down payments and carefully documented their income.

So whatever bad incentives the implicit federal guarantee creates have been offset by the fact that Fannie and Freddie were and are tightly regulated with regard to the risks they can take. You could say that the Fannie-Freddie experience shows that regulation works.

His conclusion is quoted approvingly by Economist's View, a couple of days ago.

Alas, Krugman has his facts wrong. As the Washington Post has reported:

In 2004, as regulators warned that subprime lenders were saddling borrowers with mortgages they could not afford, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development helped fuel more of that risky lending.

Eager to put more low-income and minority families into their own homes, the agency required that two government-chartered mortgage finance firms purchase far more "affordable" loans made to these borrowers. HUD stuck with an outdated policy that allowed Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae to count billions of dollars they invested in subprime loans as a public good that would foster affordable housing.

Housing experts and some congressional leaders now view those decisions as mistakes that contributed to an escalation of subprime lending that is roiling the U.S. economy.

The agency neglected to examine whether borrowers could make the payments on the loans that Freddie and Fannie classified as affordable. From 2004 to 2006, the two purchased $434 billion in securities backed by subprime loans, creating a market for more such lending.

$434 billion isn't zero, and that's just from 2004 to 2006.

I'm a bit confused about the part pointing to this blog. I don't quote that passage. In fact, I don't quote that column. In fact, I don't even link that column myself - it's only linked within a post from Jim Hamilton that I echo, and that's a post disagreeing with Krugman. So, saying I "quoted approvingly" is not exactly accurate.

The title of the post was "It Wasn't Fannie and Freddie." The point from Krugman I was referring to is (and yes, I do approve of it, and I'll explain why):

...I stand by my view that Fannie and Freddie aren’t the big story in this crisis.

Fannie and Freddie did not cause the credit crisis and nothing in the article quoted by Cafe Hayek, or anything since the article came out last June changes that.

There are two questions that are being confused in the debate over the source of the financial crisis:

1. What caused Fannie and Freddie to fail?

2. What caused the financial crisis?

Answering the first question does not necessarily answer the second. Showing that some politician, some policy, some legislation, lack of effective regulation, whatever, caused Fannie and Freddie to fail is important, we need to know why they were vulnerable when the system got in trouble, but Fannie and Freddie did not cause the crisis, they were a consequence of it.

How do we know this?

Fannie and Freddie became fairly large players in the subprime market, and they got that way by following the rest of the market down in lowering lending standards, etc. But they did not lead it down. Their actions came in response to a significant loss of market share, and it is this loss of market share that motivated them to take on more subprime loans.

We need to understand why the overall market - the part outside of Fannie and Freddie's domain - was able to lower lending standards (and increase their risk exposure in other ways as well), and how regulation which had worked up to that point failed to keep Fannie and Freddie from dutifully responding to the market pressures on behalf of shareholders by duplicating the strategy themselves, but again, they were followers, not leaders.

Tanta (via econbrowser) describes the downward plunge of the GSEs:

Fannie and Freddie .... didn't like losing their market share, and they pushed the envelope on credit quality as far as they could inside the constraints of their charter: they got into "near prime" programs (Fannie's "Expanded Approval," Freddie's "A Minus") that, at the bottom tier, were hard to distinguish from regular old "subprime" except-- again-- that they were overwhelmingly fixed-rate "non-toxic" loan structures. They got into "documentation relief" in a big way through their automated underwriting systems, offering "low doc" loans that had a few key differences from the really wretched "stated" and "NINA" crap of the last several years, but occasionally the line between the two was rather thin. Again, though, whatever they bought in the low-doc world was overwhelmingly fixed rate (or at least longer-term hybrid amortizing ARMs), lower-LTV, and, of course, back in the day, of "conforming" loan balance, which kept the worst of the outright fraudulent loans out of the pile. Lots of people lied about their income (with or without collusion by their lender) in order to borrow $500,000 to buy an overpriced house in a bubble market. They weren't borrowing $500,000 from the GSEs.

Michael Carliner continues, explaining how Fannie and Freddie took on the extra subprime debt:

Fannie and Freddie are ... subject to regulation by HUD under mandates to serve low- and moderate income households and neighborhoods. As originators and investors with more energy than brains expanded their (subprime) lending to those borrowers and neighborhoods, it was difficult for Fannie and Freddie to increase their shares. They didn't want to buy or guarantee subprime loans, correctly perceiving them to be insanely risky. Instead they purchased securities created by subprime lenders, taking only the supposedly-safe tranches. Those portfolio purchases were counted toward their obligations to lend to lower-income home buyers, but are now part of the write-downs.

Until Republicans started trying to claim that Fannie and Freddie caused the financial meltdown as a means of tying Obama to the crisis - a strategy that backfired badly when all of the embarrassing connections to Fannie and Freddie within the McCain campaign were revealed - nobody was saying Fannie and Freddie caused the crisis. Republicans simply worked backwards - they found connections between Democrats and Fannie and Freddie (never thinking to ask about their own connections), then tried to blame the crisis on Fannie and Freddie so as to make people think it was the Democrat's fault. And it's still going on despite the fact that the data doesn't support this story.

There is no excuse for the actions of the management of Fannie and Freddie, and I'm not trying to defend them or their choices, but the idea that Fannie and Freddie caused the general credit crisis is wrong.

Richard Green is dismissive of the whole notion:

Charles Calomiris and Peter Wallison blame Fannie Mae for the Subprime Mess:

Hmmmm. The loan performance on Fannie's book of business is substantially better than the overall mortgage market. And starting in 2002, Fannie Freddie (pink line) lost market share to ABS (light blue line). [The data underlying the graph is from the Federal Reserve, Table 1173. Mortgage Debt Outstanding by Type of Property and Holder.]

It wasn't Fannie and Freddie.

[Update: Follow-up argument: Barry Ritholtz: Fannie Mae and the Financial Crisis, What Caused the Financial Crisis?. For a recent academic paper at odds with the claim, see: It Wasn't Fannie and Freddie.]