Against best practices during our Cool Zone era, I'm going to make a firm prediction

about what is going to happen to the stock market in 2025:

In 2025 we will see a sharp sell off of stocks in

March. The stock market will hobble

along through the spring and summer with a full reckoning with the many

tentacled tech bubble 2.0 in the fall (probably October, maybe September).

As market predictions go, this is pretty precise. What

gives me the confidence to issue such a detailed prophesy like I'm fuckin'

Muad'dib over here? A reasonable grasp of the financial history of the

US. The US financial system is a bubble

machine and it produces bubbles with remarkable uniformity.

Let’s start with the crown jewel of American financial

disasters, the stock market crash of 1929. Here, I defer to the man who

wrote the book on it, John Kenneth Galbraith:

On Monday, March 25, the first

market day following the unseemly Saturday meeting [of the federal Reserve

Board], the tension became unbearable. Although, or rather, because Washington

was still silent, people began to sell. Speculative favorites--Commercial

Solvents, Wright Aero, American Railway--dropped 10 or 12 points or more,

the Times industrial average was off 9.5 points for the day

... On the next day, Tuesday, March 26, everything was much worse. The

Federal Reserve Board was still maintaining its by now demoralizing

silence. A wave of fear swept the market and amazing 8,246,740 shares

changed hasn on the New York Stock Exchange, far above any pervious

record. Prices seemed to drop vertically. At the low for the day

20- and 30- point loses were common place. The Times industrials

at one time were 15 points below the previous day's close. (The Great Crash of 1929, p35-36)

Galbraith goes on to describe an intervention in the form of reassuring words from Charles E. Mitchell. As head of the First National City Bank

(which later became Citibank) Mitchell offered to loan money as needed to

prevent more stock liquidations.

Mitchell soothed the animal spirits of the market enough for the bubble

to continue going through the spring and summer of 1929. Make a note of

this, it will come up again later: A financial panic in March, followed by an

intervention that keeps the system running through the spring and summer.

And then? Well, Galbraith is a better writer than I am

so I'll let him explain it. After signs of market weakness throughout

October 1929:

Thursday, October 24, is the first

of the days which---history such as it is on the subject---identifies with the

panic of 1929. Measured by disorder, fright, and confusion, it deserves

to be so regarded. That day 12,894,650 shares changes hands many of them

at prices which shattered the dreams and hopes of those who had owned

them. Of all the mysteries of the stock exchange there is none so

impenetrable as why there should be a buyer for everyone who seeks to

sell. October 24, 1929, showed that what is mysterious is not inevitable.

Often there were no buyers, and only after wide vertical declines could anyone

be induced to bid. (p99)

Anyway, I encourage you all to read Galbraith's

"The Great Crash" to get a more full sense of the future-past we are

about to stumble into. This pattern is remarkably close to the pattern of

financial crash in 1907. After the Bank of England took measures that

turned a gold inflow into the US into a gold outflow:

The effect showed up first in the

financial markets. Severe price declines occurred on the stock exchange

early in March 1907. Union Pacific stock, which had been extensively used

as collateral in finance bill operations, fell by 30 per cent within less than

two weeks. Despite every action taken by the Treasury, and a temporary

reversal in stock prices, the boom had come to an end, the National Bureau [of

Economic Research] dating the cycle peak in May 1907

...

The contraction is sharply divided

into two parts by the banking panic that occurred in October 1907. From

May to September, the contraction showed no obvious signs of severity.

Prices continued to rise; production in various lines flattened out but did not

decline seriously, and freight car loadings behaved similarly; bank clearings

held fairly stead, and there was no drastic rise in the liabilities of

commercial failures. The one significant change change was the reversal

noted earlier in gold movements from new imports to net exports. In

October came the banking panic, culminating in the restriction of payments by

the banking system, i.e., in a concerted refusal, as in 1983, by the banking

system to convert deposits into currency or specie at the request of

depositors. (Friedman

and Schwartz, Monetary History of the US, p156-157)

So what explains the similarity of the seasonal

pattern? I honestly don't have a clear understanding of why March panics

presage October collapses. The October collapses are easier to

explain. Here, I defer to Charles Kindleberger:

Periods of financial stringency and

crisis and panic (in the United States) occurred in the autumn when western

banks drew large sums of money from the East to pay for shipments of cereals. Credit

demand peaked in the autumn when the grain dealers needed money to pay the

farmers. Sprague noted that the crisis of 1873 came in September because of the

early harvest, that the outbreak of a crisis invariably came as a surprise to

the business community and that the crisis of 1873 was not an exception. The

seasonal tightness of money was well known and hence the puzzle is why it would

have come as a surprise. The ‘excessive tightness’ of money from September 1872

to May 1873 caused the railroads to borrow short-term funds rather than issue

bonds, which could have been seen as a sign of distress, and then the seasonal

tightness precipitated the crash

Distress may be continuous or it

may oscillate in its own rhythm. The crash of the Union Generale in January

1882 was preceded by three separate tense periods, in July, October, and

December 1881. The panic of October 1907 was anticipated (although Sprague

indicated its exact timing was not foreseeable) and preceded by a ‘rich man’s

panic’ in March when Union Pacific stock, the security most widely used as

collateral for finance bill operations, dropped 50 points. Markets recovered

from this blow and from the failure of an offering of New York City bonds in

June (only $2 million was tendered for an offering of $29 million of 4 percent

bonds) and from the collapse of the copper market in July, and from the $29 million

fine levied against the Standard Oil Company for antitrust law violations in

August—only to succumb to the failure of the Knickerbocker Trust Company in

October. In 1929 distress lasted from June to the last week in October (Manias, Panics, andCrashes, p101-102)

Okay, so in old-timey times financial collapses were dictated

by the agricultural liquidity cycle, even as the economy increasing

industrialized. What does that have to do with 2025? The last great

agricultural business cycle was the Great Depression, and by the time that mess

was all cleared up in 1946 agriculture was reduced to only about 10% of

GDP. Agriculture continued to shrink in importance to the US economy to

today when it makes up only about 2% of GDP. Surely this does not

generate enough liquidity pressure on the banking system to generate this

seasonal pattern. That is true, but let me remind you of how the first

tech bubble popped:

The Nasdaq reached its peak on March 9th 2000, then

had a sharp sell off. It was flat but volatile through the summer and

reached a local peak on Sept 1st. The subsequent collapse was much more

gradual than I remember. The Nasdaq did not hit a nadir until October 7

2002. Here we see a very similar pattern of stock market collapse to that

described in 1907 and 1929.

Those of you following until now and are anticipating that I'm going

to turn to 2008 are probably thinking of the bankruptcy of Bear Steans as

the March shock and the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers as the October

shock. Yeah, that's what I think, too. But the 2008 financial

crisis is different in some ways that should be pointed out. Unlike the

other collapses above, which are mostly stock market crashes (plus a bank panic

in 1907), this was a crisis in mortgage markets. Stocks don't behave in the

March/October pattern as clearly. A graph of the S&P 500 (picked because in

includes Lehman Brothers stock) is mostly a line straight down starting in

October of 2007, which is the right month but not the right year, with a slight

bump up in spring 2008.

But the stock market was responding to business

conditions. The recession is officially dated from December 2007 and this

adds too much noise to the stock market collapse to divine what is driving it

in any detail. Anyway, a collapse that

had been in motion since the start of the year got notably more rapid in the

fall of 2008. So, this is very different from a stock market perspective. However, the collapse of Bear Sterns in particular helps underscore the idea that "You can remain

insolvent a lot longer than you can remain illiquid." That, I think, is the

core of these March/October dynamics in other financial crisis.

The two overleveraged subsidiaries that eventually brought

Bear Stearns down declared bankruptcy in June of 2007. Bear Stearns was sued

that summer for misleading investors and in November the writing down of

securities would result in historically rare losses and the firms credit rating

was downgraded. But still, Bear Stearns was able to postpone the

reckoning until early March 2008, when suddenly investors rapidly withdrew

money in a classic bank run by institutional investors.

The figure below shows the seasonal response of Lehman Brothers to

the Bear Stearns collapse. Here we see a big warning: a spike in CDS spreads with a

sharp sell off of stocks in spring. This warning blip is followed by a more gradual, slow motion

collapse trhough the summer. It looks to me like the government intervention to push an orderly sale of Bear Stearns to JP Morgan Chase gave Lehman Brothers breathing room. Not pictured is the catastrophic collapse in September

2008.

Here, I quote liberally from Wiggins,

Pointek and Metrick, 2019:

After the demise of Bear Stearns,

Lehman began casting around for a long-term strategy that would secure the

firm’s future and allay the market’s fears. It considered several options,

including increasing equity, spinning off “toxic” assets (generally real-estate-related

assets) into a separate publicly held corporation, and discussing a sale of the

firm, or a capital infusion, with the Korea Development Bank. Lehman was

successful in raising $6 billion in equity in June 2008, despite a reported

second quarter loss of $2.8 billion, its first since it went public, which was

caused in part by a $3.7 billion write-down on its portfolio of

mortgage-related assets and leveraged loans. But this was not enough to quell

the rumors.

A solution failed to materialize,

and on September 10, 2008, Lehman announced that it expected $5.6 billion

dollars in write-downs on its toxic assets and an expected loss of $3.93

billion for its third quarter. It also announced that it planned to spin off

$50 billion of its toxic assets into a publicly traded corporation in order to

separate them from the remaining “healthy” firm.

The news did not have the positive

effect that Lehman desired. The rating agency Moody’s Investors Service

announced that it planned to lower Lehman’s debt ratings if a “strategic

transaction with a strong financial partner” did not occur soon. Even though

Lehman continued to desperately seek such a partner, with the intercession of

the U.S. Treasury and other government agencies as described below in Regulator

Nonaction, ultimately it failed to secure a firm commitment within the next

week. As a result, it was unable to fund its operations for opening on

September 15, compelling it to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. (See

Lehman Brothers press release dated September 10, 2008 and Lehman Brothers

press release dated September 15, 2008.) (Wiggins,

Pointek and Metrick, 2019)

Now, shoehorning 2008 into my seasonal theory makes it clear

that I can’t offer a causal mechanism for why this seasonality continues to

happen. Finance bros come home from the Hamptons in September? The 2008 example highlights the seasonality of financial reporting. Maybe

policy interventions follow this seasonal pattern by coincidence? IDK. The

soothsayer didn't need to know it would be 60 senators with knives to issue her

warning to Caesar. Though, in all fairness, less poetry and more

specificity probably would have been more convincing.

Now, I feel pretty confident about my prediction. But, maybe I am a year or two ahead of myself. However, let’s assess the state

of the country’s economy. The rats are eating at the federal government's

COBOL code. There is also a growing chorus of voices who point out it is

impossible for AI to supply the expected return on investment. As if to

confirm these voices AI

ads featured prominently in this years Super Bowl.

As well, as a rough estimate, post-WWII recessions occur

within 12-18 months of when the Fed tightens the hardest. That is, when

the Fed Funds reaches it peak. The Fed Funds rate reached 5.25% in July

of 2023. To the extent similar pressures from the cycle of debt refinance and

the drying up of liquidity exists as they have, we are overdue for downward

pressure on stock prices. Liquidity will

dry up and earnings will be disappointing. Spring 2025 is likely time for

the pressure to start popping out the weaker rivets of our boiler of a

financial system. The financial system will hiss and bulge through the

summer with the catastrophic failure and spectacular explosion coming in the

fall.

The economic dynamics after the stock market crash, I think,

are much harder to soothsay thanks to the liminality of the structural shift that

powers a Cool Zone. I think a financial crash will be inevitable, but how

effectively policy makers handle this crash remains a big unknown. Will the

2025 collapse look more like 2001, which was associated with a mild real economy recession? Or will it be the

catastrophe of 2008?

This unknown is mostly about how the Fed and federal

government with respond. I think no matter what this impending economic crises will be

used to continue the redistribution of American wealth upwards. The open question for the federal government

will be what policy mix emerges. There will

be push and pull between the Hooverite wing of the Republican Party and Trump

who gleefully and proudly sent signed checks to almost all Americans during

Covid. Even then, to the extent that

there is competent counter-cyclical policy it will likely be to keep Americans

in their treats enough so they don't notice the slowly boiling water around

them.

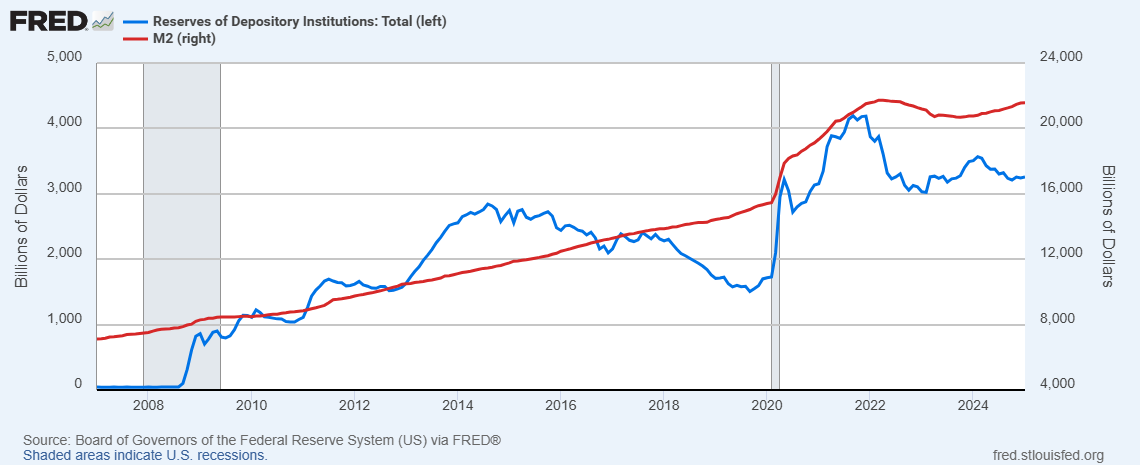

How this crisis plays out for the Fed is also, I think, very

up in the air. The Bernake playbook for dealing with crises has proven a

remarkable success in 2008 and during Covid. Its main success, though,

was in insulating the wealthy from the consequences of their speculative

activity. Not only were the wealthy protected but they are thriving. The

share of the top 1% is about 2 percentage points higher that it was in 2007 on

its way back up to 1929 levels.

Will the Bernanke playbook be enough to maintain the

stability of the system in a way that permanently entrenches modern neoliberalism?

Or, will the zero lower bound go the way of the gold standard? The

economic historian Peter

Temin described the inability of policy makers to see past the

"gold standard orthodoxy" as the root cause of the severity of the

Depression. As also with the chronic inflation at the end of the New Deal

Order, will the neoliberal policy regime simply not be able to imagine the

solutions to the crisis it finds itself in? I think this is very likely and the impending crisis will drag on and

worsen until the political system catches up to provide a solution.

But that's all a conversation to have later. See you when I

blast social media with this post in the fall.